Northwestern College has joined the University of Iowa and Iowa State as the only higher education institutions in the state with a gene sequencer.

An anonymous donor funded the purchase of the $100,000 MiSeq model made by Illumina. The sequencer is a scientific instrument that is capable of determining the precise order of the nucleotides—abbreviated as A, G, C and T—within a strand of DNA. It was delivered and installed in November.

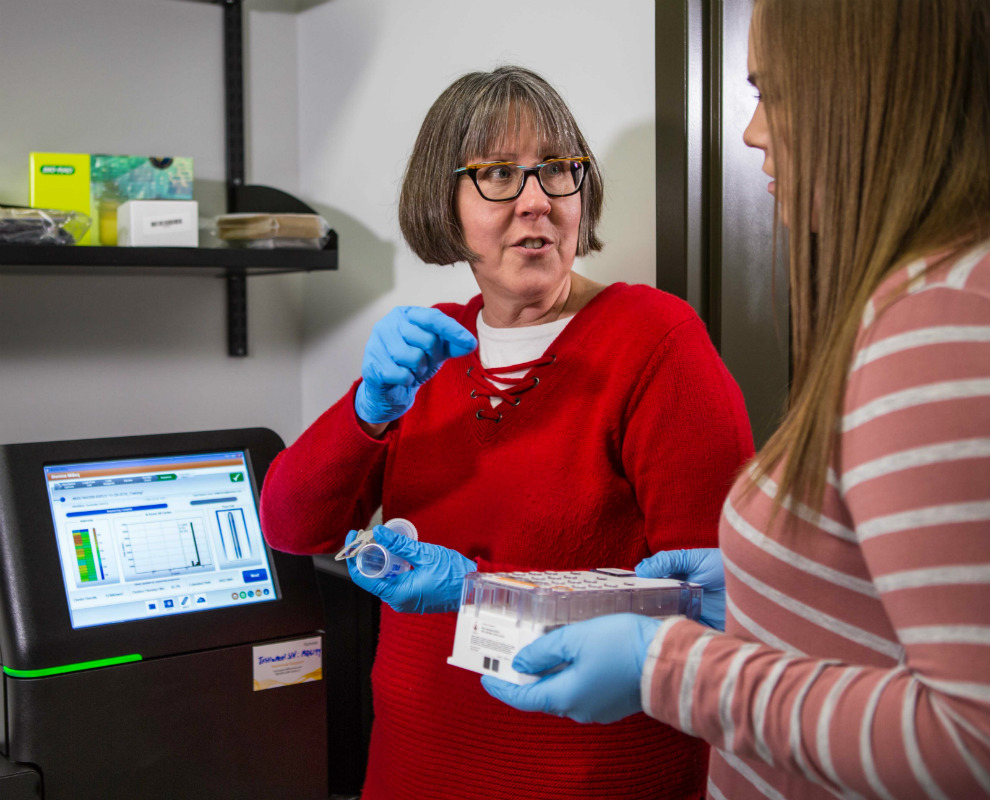

“We want to use this both for research and for teaching,” says Dr. Sara Sybesma Tolsma, professor of biology. “It’s a very sensitive piece of equipment and it’s expensive to run, but we’re going to involve students as much as we can and still be good stewards of the costs associated with the sequencer.”

Tolsma says she and her colleagues never dreamed that owning a gene sequencer was a possibility for their department. However, when Northwestern was raising $24.5 million for its new DeWitt Family Science Center, an alum of the college offered to provide one.

Tolsma is excited about the impact the sequencer will have on Northwestern’s science students.

“To be able to show them where we put the sample and what the flow cell looks like and how it works—that makes it more real for them and they understand it better,” she says.

Such access to a gene sequencer is unusual for undergraduates. Tolsma’s son is a second-year graduate student at a major public research university. Sequencing is part of his work on a doctorate in genetics, but he never gets to touch the equipment. Instead, he hands his DNA samples to the university employee who runs the sequencer and waits for the results.

Tolsma anticipates a variety of ways Northwestern will use its gene sequencer. The college is part of the national SEA-PHAGES program, which is designed to interest undergraduates in scientific research by making them part of a global effort to discover phages, viruses that infect bacteria. All of the students in Microbiology want to have the phages they discovered sequenced, but that process costs $250 per phage when done by another institution. By having its own sequencer, Northwestern will be better able to meet that demand.

Tolsma and Dr. Laurie Furlong, another member of Northwestern’s biology department, will also use the sequencer to research the gene expression of mayflies in different environments. Their chemistry department colleagues, meanwhile, are interested in confirming gene mutations made in site-directed mutagenesis.

“This machine isn’t powerful enough to do a human genome, but it’s way more powerful than what we need to do a simple virus, like a phage,” Tolsma says. “So it’s doing what we need it to do today, and it will do what we want it to do tomorrow.”